Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

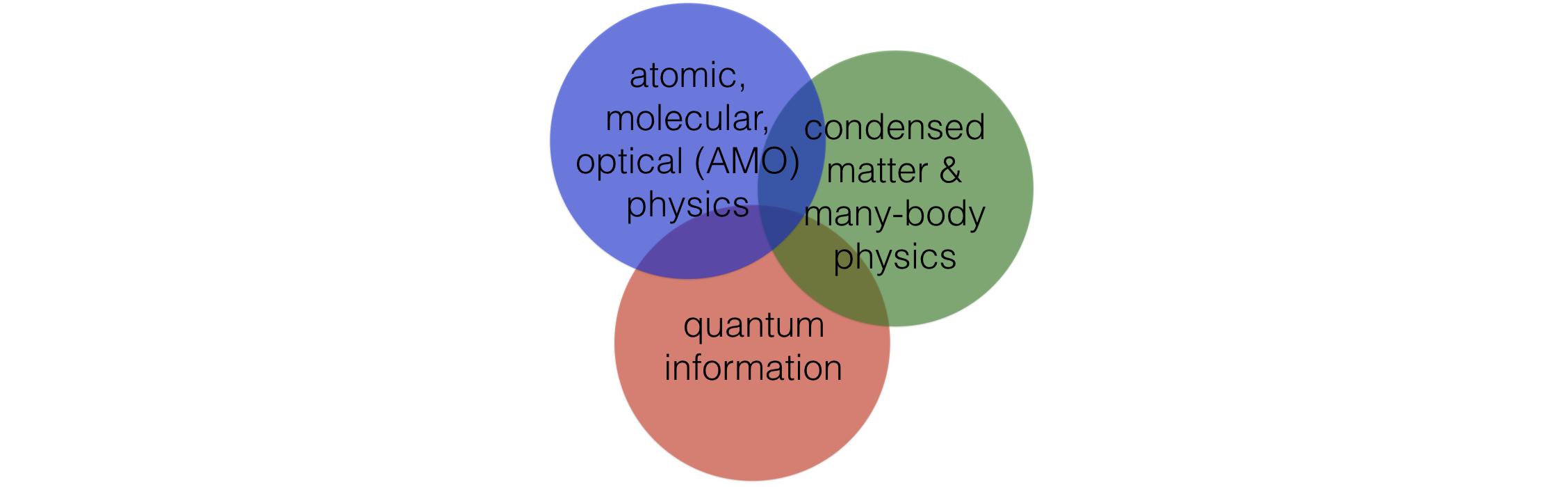

We are a theoretical research group working at the interface of quantum optics, quantum information science, and condensed matter physics.

Postdoc and graduate student positions available: email av[group leader's last name]@gmail.com

JQI Graduate Student Is Finalist for Hertz Fellowship

Elizabeth Bennewitz, a first-year physics graduate student at JQI and QuICS, has been named a finalist for a 2022 Hertz Fellowship. Out of more than 650 applicants, Bennewitz is one of 45 finalists with a chance of receiving up to $250,000 in support from the Fannie and John Hertz Foundation. The fellowships provide up to five years of funding for recipients pursuing a Ph.D.

Enhancing Simulations of Curved Space with Qubits

One of the mind-bending ideas that physicists and mathematicians have come up with is that space itself—not just objects in space—can be curved. When space curves (as happens dramatically near a black hole), sizes and directions defy normal intuition. Understanding curved spaces is important to expanding our knowledge of the universe, but it is fiendishly difficult to study curved spaces in a lab setting (even using simulations). A previous collaboration between researchers at JQI explored using labyrinthine circuits made of superconducting resonators to simulate the physics of certain curved spaces. In particular, the team looked at hyperbolic lattices that represent spaces—called negatively curved spaces—that have more space than can fit in our everyday “flat” space. Our three-dimensional world doesn’t even have enough space for a two-dimensional negatively curved space. Now, in a paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters on Jan. 3, 2022, the same collaboration between the groups of JQI Fellows Alicia Kollár and Alexey Gorshkov, who is also Fellow of the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science, expands the potential applications of the technique to include simulating more intricate physics. They’ve laid a theoretical framework for adding qubits—the basic building blocks of quantum computers—to serve as matter in a curved space made of a circuit full of flowing microwaves. Specifically, they considered the addition of qubits that change between two quantum states when they absorb or release a microwave photon—an individual quantum particle of the microwaves that course through the circuit.

In a Smooth Move, Ions Ditch Disorder and Keep Their Memories

Scientists have found a new way to create disturbances that do not fade away. Instead of relying on disorder to freeze things in place, they tipped a quantum container to one side—a trick that is easier to conjure in the lab. A collaboration between the experimental group of College Park Professor Christopher Monroe and the theoretical group of JQI Fellow Alexey Gorshkov, who is also a Fellow of the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science, has used trapped ions to implement this new technique, confirming that it prevents their quantum particles from reaching equilibrium. The team also measured the slowed spread of information with the new tipping technique for the first time. They published their results recently in the journal Nature.